To compensate for these effects, the algorithm first automatically corrects for tilted faces, turned heads and inconsistent lighting, then applies the computed shape and appearance changes to the new child’s face. Real-life photos of children are difficult to age-progress, partly due to variable lighting, shadows, funny expressions and even milk moustaches. “When shown images of an age-progressed child photo and a photo of the same person as an adult, people are unable to reliably identify which one is the real photo.” “Our extensive user studies demonstrated age progression results that are so convincing that people can’t distinguish them from reality,” said co-author Steven Seitz, a UW professor of computer science and engineering. In an experiment asking random users to identify the correct aged photo for each example, they found that users picked the automatically rendered photos about as often as the real-life ones.Ī single photo of a child (far left) is age progressed (left in each pair) and compared to actual photos of the same person at the corresponding age (right in each pair). The researchers tested their rendered images against those of 82 actual people photographed over a span of years. These changes are then applied to a new child’s photo to predict how she or he will appear for any subsequent age up to 80. An algorithm then finds correspondences between the averages from each bracket and calculates the average change in facial shape and appearance between ages.

FACE MORPH AGE PROGRESSION ONLINE SOFTWARE

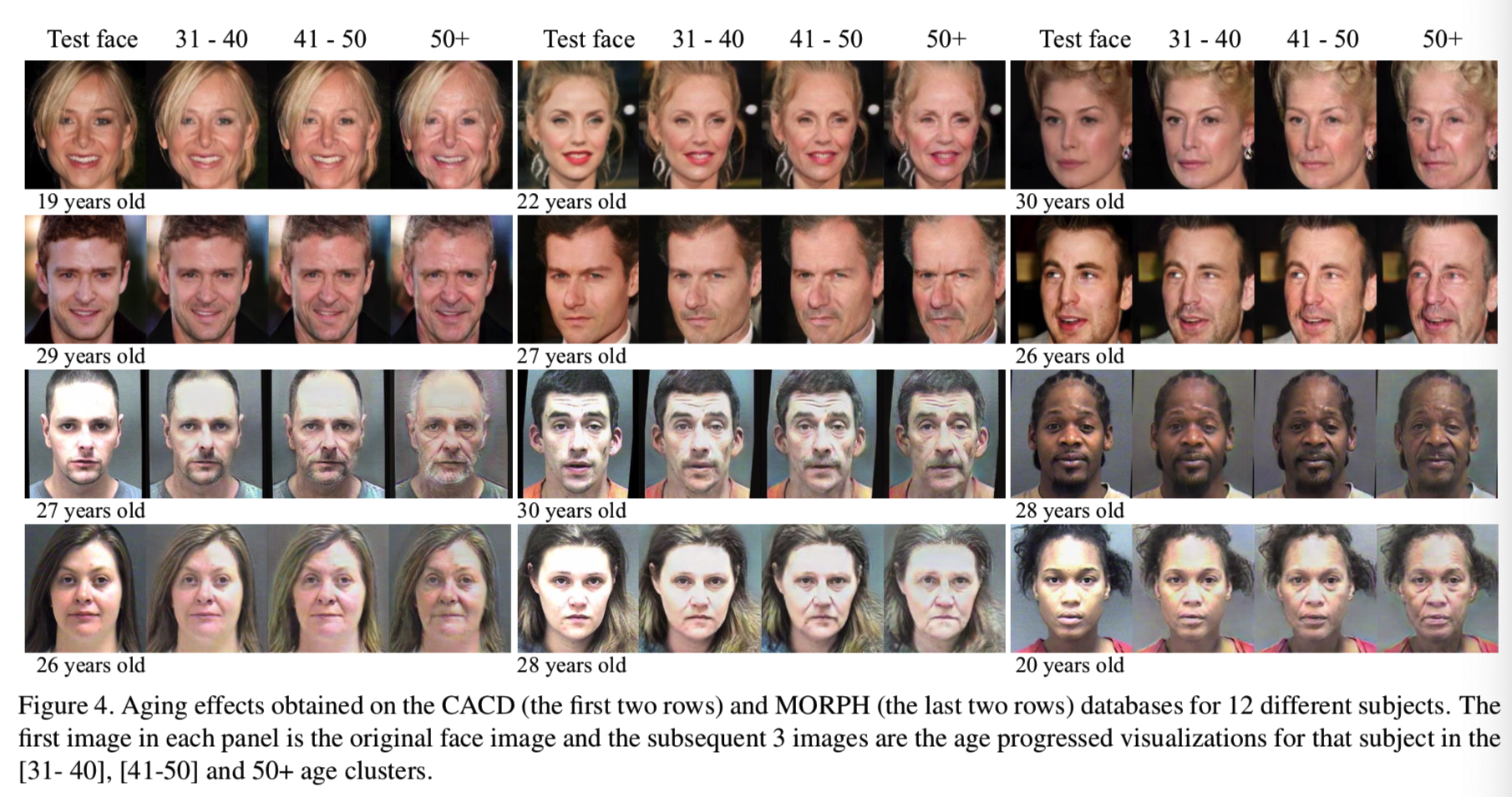

More specifically, the software determines the average pixel arrangement from thousands of random Internet photos of faces in different age and gender brackets. This technique leverages the average of thousands of faces of the same age and gender, then calculates the visual changes between groups as they age to apply those changes to a new person’s face. The shape and appearance of a baby’s face – and variety of expressions – often change drastically by adulthood, making it hard to model and predict that change. The work - which was funded by Google and Intel - is to be presented at the IEEE Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition conference in June.See more examples of age-progressed photos. When shown images of an age-progressed child photo and a photo of the same person as an adult, people are unable to reliably identify which one is the real photo." "We've invented a method for "lighting-aware flow estimation" between such photos, and this opened up a huge amount of applications, the key in which is to use "big visual data" for novel face modelling and synthesis.Ĭo-author Steven Seitz said in a statement: "Our extensive user studies demonstrated age progression results that are so convincing that people can't distinguish them from reality. with unknown lighting, viewpoint and expression. Kemelmacher-Shlizerman told .uk that the biggest challenge was coming up with a method for "completely automatic analysis of face photos 'in the wild'", i.e. The study authors say that future improvements for the work include: modelling wrinkles and hair whitening to enhance the realism of older subjects, increasing the range of ethnicities, and having a database of heads and upper torsos of different ages in order to apply the same technique to.

The results seemed to show that for ageing young children, the University of Washington's technique outperformed all prior work.

37 percent (out of 8,916 votes) said that the University of Washington team's approach was more likely to be the older baby, 44 percent saying the actual image was more likely.ġ5 percent of people said that both were equally likely to be the adult version of the baby, while five percent said neither were likely. The results seem to show that humans identified the generated image as the older version almost as often as they identified the actual older image. The volunteers had to say which of the two older photos were more like the baby. One picture would be an individual as a baby, and the two additional photos would be that person at a specific age (say 25) - one generated by the software and one actual image of that person at that age. This was put to the test by showing three pictures to human subjects (through Amazon's Mechanical Turk). This allowed them to see how effective the software was at accurately ageing the children. To check the efficacy of the system, the team fed in child images of individuals for whom they also had adolescent and adult images.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)